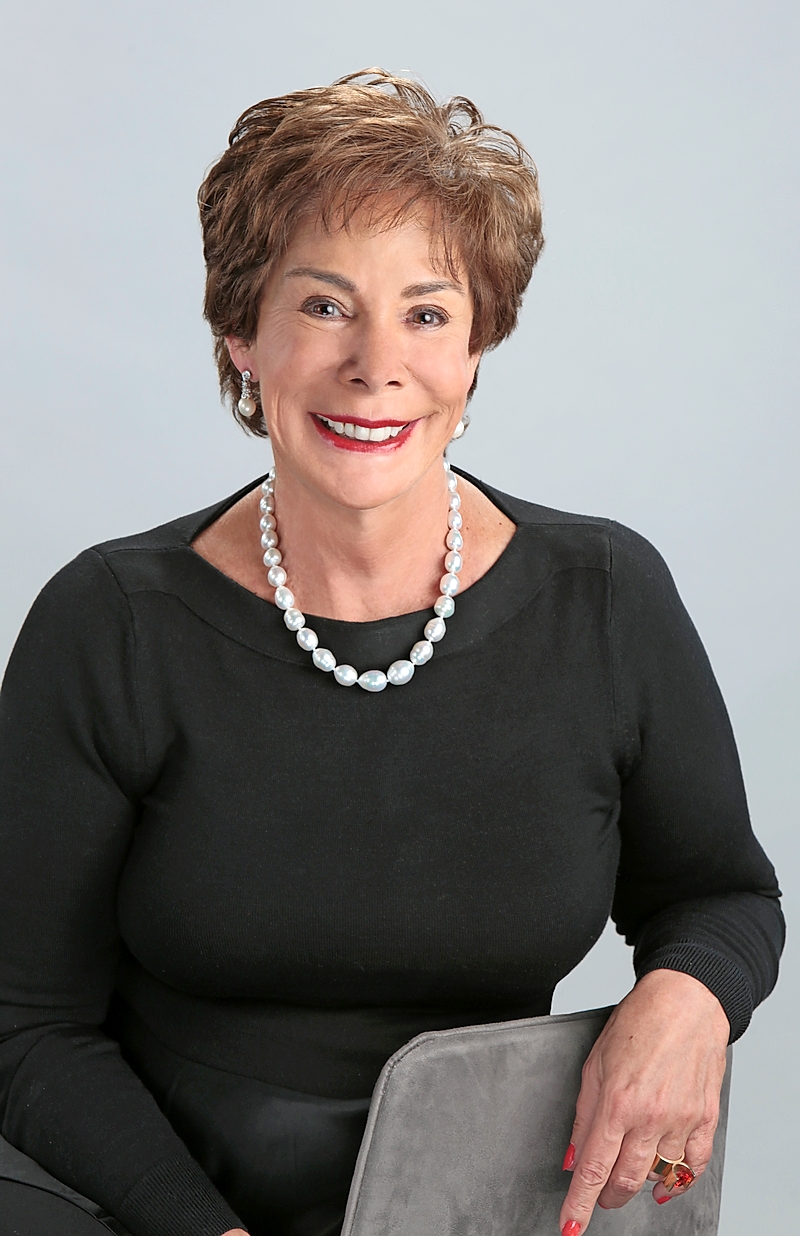

Sound Advice

By Hilary Decent

January 2018 View more Humanitarian

Tell me again you love me, Momma, I can hear you now.” The simple phrase from a seven-year-old boy who had lost his hearing after recovering from brain cancer meant everything to Dr. Ronna Fisher.

“It was one of the most gratifying moments of my life. Everyone in the room was crying,” she recalls. “I knew then I had found the purpose for my foundation; these children with brain cancer have a need no one is filling.”

Fisher started her Fisher Foundation for Hearing Health Care nonprofit in 2005; it provides hearing aids to anyone who cannot afford them, as the costs are not usually covered by insurance.

In addition to providing a public service, she has also helped servicemen, providing custom-fit aids to protect them from the noise of combat, while still allowing them to hear commands. But it’s the children she especially wants to help.

“Seventy percent of all children with brain cancer will suffer irreversible hearing loss,” Fisher says. “Doctors may have saved their lives, but then they find they can no longer communicate with their peers or family following treatments like chemotherapy and radiation. If these kids don’t get hearing aids immediately, they will fall behind in school and it will affect their learning and lives ahead.”

For Fisher, the plight of hearing loss is personal. Her father, who died at the age of 53, suffered hearing loss all of his adult life after contracting rheumatic fever as a child.

“It got worse and worse,” she says. “As a teen, I admit I had little patience for him. The words he probably was able to make out most frequently were ‘Never mind, it doesn’t matter,’ when we became frustrated that he couldn’t hear us.”

After grad school, Fisher decided to become an audiologist. She received her doctoral degree in audiology from the Pennsylvania College of Optometry, is a fellow of the American Academy of Audiology, has earned the Certificate of Clinical Competence from the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association and is an active member of the Academy of Dispensing Audiologists, American Tinnitus Association and the Illinois Academy of Audiology.

“Dad missed so much of my life and it didn’t have to be that way,” she says. “He and my mother used to go out every Saturday night for dinner with friends or the theater, but as his hearing got worse, he stopped. He had been so outgoing and fun. He’d sit on his own to watch TV because it was too loud for the rest of us. He was told that hearing aids wouldn’t help him because in those days they only amplified the sound.”

Fisher knows that if someone is hard of hearing it affects the whole family.

“My mother would accuse him of not listening and not paying attention to her,” she recalls. “His colleagues thought he was ‘stuck up’ when he didn’t acknowledge their greetings. Clients were disgruntled when he misheard what they said. His children, including me, were impatient and angry at having to repeat everything all the time.”

Today’s hearing aids are far more sophisticated, but technology comes at a high price: Basic hearing aids are around $500, but they can cost up to $3,500 each.

“You hear with your ears but listen with your brain, and every brain is different,” Fisher explains. “We can fine tune the amount and kind of sound each brain processes best.”

Fisher owns five Hearing Health Care Centers in the Chicagoland area, including a newly opened facility on Naper Boulevard.

“It would kill me when people came in for help and couldn’t afford it,” she says. “Hearing aids are the only treatment for hearing loss in 95 percent of cases.”