Alfresco Artistry

By Naperville Magazine

June/July 2020 View more Featured

By Peter Gianopulos

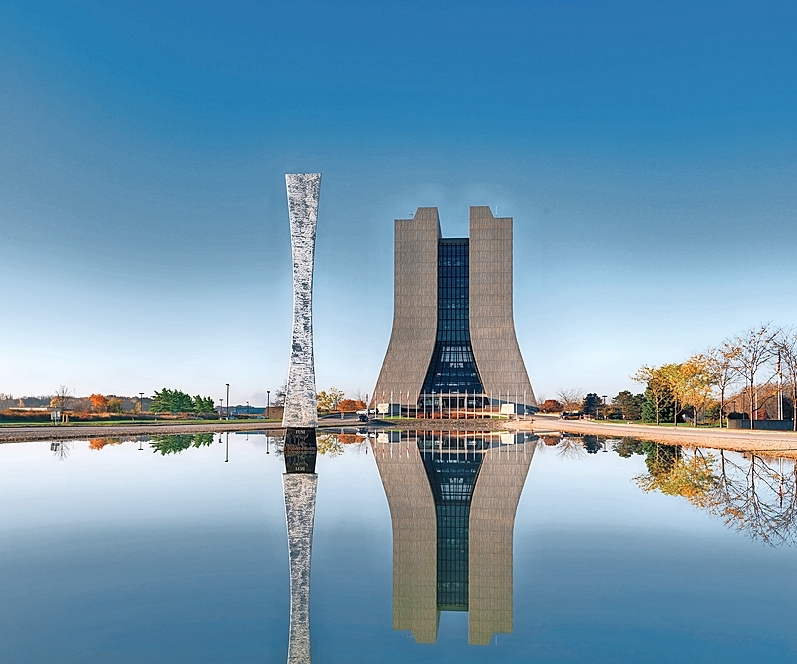

Fermilab, Batavia

Long before tech firms began using sleek architecture as recruiting tools and academic journals started exploring how art can spur creativity, physicist Robert R. Wilson was probing the hidden connections between science and sculpture.

Much ink has been spilled about Wilson’s achievements. As the inaugural director of Fermilab, from 1967 to 1978, Wilson worked to untangle the twin Gordian knots of space and time, producing theories that, for most of us, are as dizzyingly opaque as the inner workings of a particle accelerator.

But those who visit Fermilab’s campus in Batavia—where Wilson oversaw the creation of an impressive collection of outdoor sculptures—will find his outdoor artwork to be a far more accessible mash-up of science, nature, and art.

Note the lab’s “Mobius Strip” sculpture (below), which was constructed from 3-by-5 slats of stainless steel that Wilson welded together himself. Or the stunning 32-foot-tall “Hyberbolic Obelisk” standing guard over the central laboratory (far left), which seems to glorify both the beauty of human craftsmanship and the inescapable pull we feel to push our ambitions further skyward.

As lab archivist Valerie Higgins notes, Wilson was a committed conservationist who prevented employees from cutting down a single tree on the lab’s grounds without his permission. Go back further, says Higgins, and you’ll discover Wilson studied sculpture at the Accadamia di Belle Arti di Roma.

“He was undoubtedly a Renaissance man,” she says, which may explain why the Fermilab sculptures project such powerful emotions and lofty thoughts. Collectively, perhaps they suggest that the distance between art and science, two pillars of human existence, is not so great.

Century Walk, Naperville

When it comes to outdoor artwork, Naperville is as aesthetically dense as a Richard Scary drawing. There’s artwork everywhere.

The more than 50 nooks, squares, and alcoves that house outdoor pieces along the town’s Century Walk aren’t meant to be mere eye-candy. Each piece of art is meant to tell a story about the history and values of the town. Together, they create a dazzling pop-up history book like no other.

And there’s an interesting origin story hiding within these outdoor storybooks that involves local lawyer Brand Bobosky, without whom none of this would have be possible. In 1994, while he was paging through a Smithsonian magazine, Bobosky came across a story about a struggling lumber mill town in British Columbia called Chemainus, which attempted to boost its sagging spirits with outdoor artwork.

Long intrigued by the intersection of art and history, Bobosky launched a one-man crusade to launch a similar initiative for his beloved Naperville. Soon, Abe Lincoln sculptures were taking up bench space in breeze-swept parks and a giant mural depicting a local parade brightened up an often-overlooked brick alleyway.

“I think public art should reflect the fiber and character of a community,” says Bobosky. “It can tell interesting stories: These people were here, they built this place. And now they won’t be forgotten.”

Art Museum, Elmhurst

If art has the power “move” us in incalculable ways, who’s to say it can’t also guide our physical movements, as well?

John McKinnon, the executive director of the Elmhurst Art Museum, is proud of his city’s art—whether it’s his own museum’s revolving exhibits, the city’s murals, or the impressive collection at nearby Elmhurst College. But how, he wondered, might the outdoor art be able to draw the shy and uninitiated to take a closer look?

The answer: improved curb appeal. In many ways, the museum’s outdoor pieces are meant to draw visitors away from the sidewalk and toward the city’s art.

Early inspiration came from local multi-media artist David Wallace Haskin, whose frequent walks across the museum’s lawn inspired the 2015 creation of “Skycube,” (below) one of the museum’s most beloved sculptures.

At first glance, the three-ton steel and glass square appears to be a giant LED screen, streaming zen-inducing clips of clouds and sunlight in motion. It beckons streams of giggling children and awestruck adults wanting to touch the screen. But upon closer inspection, whether by circling the piece or by tucking their heads inside the mysterious square, it’s clear there’s no screen nor digital tricks at work. The images are merely mirrored reflection of the sky above, a gesture that brings the heavens down to eye level for all to see from a different perspective.

It’s not the only outdoor piece that encourages passersby to reject stasis in favor of exploration and movement. Matthew Hoffman’s diabolically simple “You Are Beautiful” sign, which is attached to the museum façade, simultaneously affirms inner beauty and suggests something equally beautiful lies inside.

Others can’t help but peer inside the glassy façade of the McCormick House,

a 1952 Mies van der Rohe single-family home that sits on the museum grounds.

Still others run their fingers along John Nester’s “Art from the Heart,” a series of four contoured clay pillars that pay tribute to local art programs.

“Art can be an invitation,” says McKinnon, whose pieces celebrate Midwestern artists. “We want our outdoor art to help beautify the city and encourage people to come inside and take a look.”

Butterfly Wing Mural, Lombard

For a moment, case aside every dictum, decree, and directive ever posted on an art gallery wall. To properly experience Kelsey Montague’s 13-foot-tall floral-patterned butterfly wing mural at Yorktown Center, you’ll want to undergo a reverse metamorphosis. Go back and find your inner-kindergartener because this piece wasn’t built for gazing and contemplating. Montague’s wings, aptly named “What Lifts You,” were meant to be played with—to be slipped on as if they werea vast immovable Halloween costume.

So go ahead, don’t be shy. Touch it. Pose with it. Photobomb yourself inside of it. And then share your happy selfies on every social media platform you can download. That’s Montague’s chief aim: to create wearable, Instagram-ready street art that acts as a joyous crosscurrent to the tidal waves of negativity that so often dominate social media.

Montague’s winged murals, which have transformed drab walls from Hong Kong to Cape Town into glowing auras of light, are—by her own admission—incomplete without the viewer’s engagement.

“I create interactive art that invites a person to become a living work of art,” says Montague. “I don’t believe art should be separated from the human experience—instead human experience should have a hand in creating the art.”

By choosing to paint her Yorktown wings on a wall within the Self-Care Precinct, near fitness and beauty shops, she hoped to generate feelings of regrowth, freedom, and inner beauty.

“My work is all about getting people to stop and reflect on what’s important to them,” she says. “I genuinely want them to feel lifted up—even if only for a moment or two.”

Public Art Tour, Elgin

When it comes to indoor artwork, we rarely consider the importance of the spaces that surround it. What lies behind becomes an afterthought; what’s in the foreground is all we see.

Not so in Elgin. Consider the rainbow-colored “1835 Exhibit” sculpture that brightens the city’s river walk (see cover). Davis McCarty’s piece is a geometry teacher’s dream: a collection of multicolored plexiglass shards that erupt from a star-shaped core, as if McCarty had frozen them in mid-explosion.

Depending on the position of the sun—not to mention the direction from which visitors approach the piece—the sculpture spills different blocks, quivers, and polygons of light onto the nearby sidewalk. The piece’s beauty is a direct product of its riverfront surroundings.

When the Elgin Cultural Arts Commission funded its self-guided public art tour in 2016, it wanted to push against the tired notion that art is an elitist endeavor. By using urban spaces less as backdrops and more as co-creators, the commission hoped to create a three-way dialogue between the town, the art, and residents.

With that aim, Elgin commissioned mural artists to create high art in what some might consider ordinary places. Melina Scotte’s vibrant “Las Raices del Alma” (“Roots of the Soul”) (upper left) depicts a woman in repose, but applies bright yellows, teals, and oranges onto a drab parking deck. And consider the striking “Shape of Happiness” sculpture by Ben Pierce (lower left), which suspends giant circles in the air. It’s meant to capture the fevered joy of children chasing bubbles, but was strategically placed in a spot designed to encourage people to sit on benches and slow down their daily lives.

Art in Public Places, Aurora

When Aurora’s new public art app launches this summer, it will guide locals and visitors alike on art-themed “treasure hunts” across downtown. Over the years, Aurora has amassed an impressive collection of outdoor art pieces, from both local and internationally acclaimed artists, but the town lacked a wayfinding tool capable of directing art lovers to its many treasures.

Not only will the new app allow for customized art urban hikes, it will provide detailed information about each piece, from artist bios to historical context—thus allowing viewers to delve deeper into the creation and meaning of each piece.

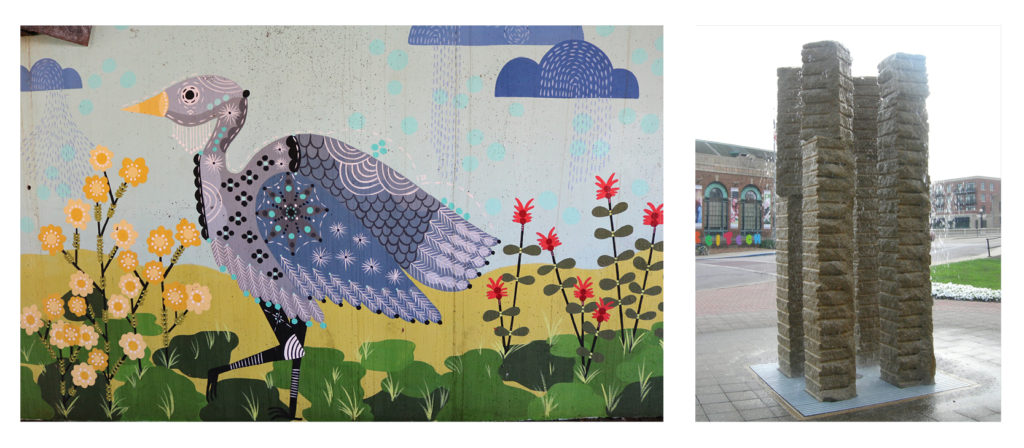

Those who visit Bunnie Reiss’s “Great Blue Heron” mural under Aurora’s New York Street bridge (lower left), for instance, can learn more about the folksy style of the Los Angeles–based international artist, as well as the local flora and fauna that she incorporated into the piece. Others who visit one of the city’s many decorated utility boxes may discover a local artist worth hiring or championing.

Jennifer Evans, Aurora’s director of public art, sees the app as the first step in a far more ambitious augmented-reality program. Think “Pokemon Go—Art Edition.” She foresees a future when pedestrians can point their smartphones at a sculpture and generate digital rainfalls or rainbows around the sculptures. Others may want to grab a swoosh of paint from a mural and glide it around their screens like a magic carpet. Or better yet, come across a poem and listen to its author read a stanza or two aloud

“We’re trying to look at downtown Aurora as a giant game board, as one composition with many parts,” says Evans, who is a large-scale multimedia painter herself.

Evans says her interest in interactivity was inspired by many of Aurora’s existing pieces, including Christian Tobin’s “Isaac 2/Swimming Stones,” a sculpted fountain that sets four 12-foot-tall granite obelisks upon a pillow of water (lower right). The tops of each column twist and dance, releasing chaotic sprays onto giggling children below.

Might it be possible, she wondered, to provide adults that same gleeful love of art?

“What’s exciting about downtown Aurora, in terms of its art, is how dense it is,” says Evans. “Sometimes, it’s hard to see all of those layers, but they are there. We want to help move people across the board so they can enjoy them all.”