Creative Forces

By Lisa Arnett

August 2022 View more Featured

“Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.” This oft-quoted line from a 1905 George Bernard Shaw play couldn’t be further from the truth for these three creatives who balance pursuing their chosen art with teaching it to the next generation. Whether through the written word, fleeting melodies, or swaths of color that breathe life into city streets, these creators and educators are making their mark here in the west suburbs and beyond.

Rafael Blanco

THE PUBLIC ARTIST

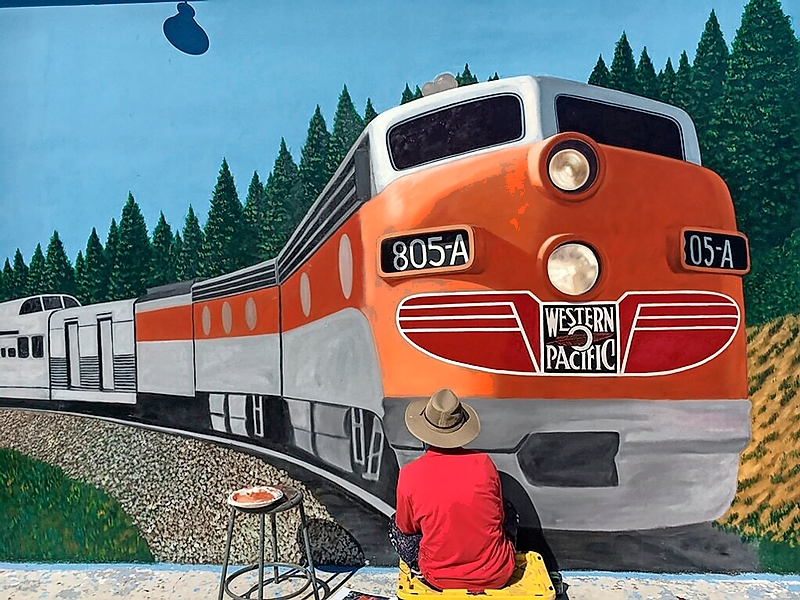

Aurora resident Rafael Blanco, 40, creates large-scale murals in public spaces and also works as an assistant professor at Elmhurst University.

Last summer he painted the largest single public art project in Aurora,

a mural (above) called Diversity in Technology, on the side of the former Aurora National Bank building at 105 East Galena Boulevard.

An early appreciation for art: Blanco was born in Alicante, a city in southern Spain, and grew up in Madrid. “I’m the artist I am today because of my mother,” he says. “She exposed me at a very early age to the National Museum of Prado, to all the big museums in Madrid.” Though she was not an artist herself, her father—Blanco’s grandfather—was a sculptor and had instilled in his family an appreciation for art. “It was normal for her to take me to these places every other week. And I thought it was normal, too—I thought every kid in the world had access to these paintings and amazing artwork.”

Thinking of You, Rockford in Rockford, Illinois

Art as communication: As a child, Blanco struggled with talking in front of others. “Speaking, for me, was always difficult, and I used to stutter a lot,” he says. “I was afraid of speaking, but I was not afraid of drawing Through the years, I learned how to communicate better, though I still stutter; it depends on the day. But that visual language was very universal and embedded in me as a way of communicating.”

He’s a good sport: Though Blanco enjoyed art, growing up he wanted to be a professional tennis player. Two of his siblings earned tennis scholarships to American universities, so he followed suit and secured a scholarship to play tennis at Florida Southern College. The fine-arts classes he took there, however, enticed him to pursue art as a career. “They taught me more than drawing; they taught me how to see and how to perceive like an artist does—it was almost something magical,” Blanco says. “So painting and drawing became my full passion, and once I graduated, I felt that tennis was no longer that obsession that I had before. That is one of the things that I like about teaching at [Elmhurst University] today. For me, it is a turning point in anyone’s life. You have to choose your profession for the rest of your life. And seeing the big influence my teachers had on me, it is something that I enjoy being a part of.”

Western Pacific Mural in Portola, California

If at first you don’t succeed: After graduating with a bachelor’s in studio art, Blanco wanted to pursue an MFA. However, it took a while to find a program that would accept him. “For seven years, I applied to several schools around the country and I got denied, denied, denied,” he says. “I can say that I am very stubborn. After my third or fourth year applying and getting 12 letters a year of denial, I decided to quit painting for a while.” That was easier said than done. “I couldn’t quit. There was this need that I physically and mentally felt, and at that moment, I understood that I was painting for the wrong purpose. I had been painting at that point for the acceptance of others, and if I wanted to pursue painting for the rest of my life, that acceptance had to be secondary.”

His unlikely moment of inspiration: Blanco was living in Oakland, California, and coaching tennis to support himself when he received an invitation to a flamenco show in San Francisco from the Spanish Consulate. “Honestly, I have never been interested in flamenco,” Blanco says. “Back home, flamenco is seen as for the tourists. But I was homesick and I wanted to go meet more people from my country.” At the show, he was awestruck by the dramatic lighting and the dancer’s passionate facial expressions. Now on the other side of the world, this tradition from his homeland inspired him to paint a series of portraits. This project ultimately resulted in his acceptance to the MFA program at University of Nevada, Reno.

From the canvas to the wall: After graduating with his MFA, Blanco thought he’d continue to show his art in galleries. All that changed when he was invited to participate in a 24-hour mural marathon in downtown Reno. “There were seven artists working on seven panels of 15 feet high by 20 feet wide,” he says. Blanco painted for 24 hours straight—“I think I ate maybe half of a sandwich”—and found himself captivated by the process of creating public art. Painting with oils on canvas in his studio was slow and deliberate, completed in solitude. With mural painting, he had to work quickly on a massive scale, at the mercy of the outside elements and the distractions of passersby. “[After creating art] in the studio, you had your exhibition and people come to your reception and they are looking at the finished work. They have no idea how you did it,” he says. “Here, the viewer becomes part of the artwork because they are seeing the process. So people would ask me questions, and I would explain my process, and I was really able to connect with people on a very different level. I love painting people. My work is about humanity, so being able to share that at the same time that I was creating work, it was fascinating.”

Making time for murals: Blanco was looking for a job with the flexibility for him to pursue more public art projects. That’s what brought him to Elmhurst University, where he is able to teach painting and art history and travel for mural projects on school breaks. He’s since painted murals in California, Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Indiana, Colorado, Maryland, Texas, and right here in Illinois. “It is amazing to be able to travel to a new place and create a work of art that is going to beautify, that is going to improve an area of that community,” Blanco says. His work is site specific, meaning it’s conceived for each space in particular. “I see myself as doing the public a service, and that’s why I love the term ‘public art.’ The work I do is not about me. I try to make artwork that is deeply connected to the place that I am going, so that way, it is meaningful for that place.”

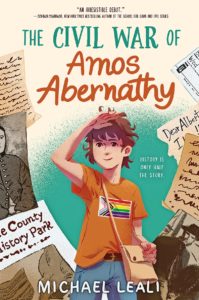

Michael Leali

THE DEBUT NOVELIST

These days, when 32-year-old Michael Leali isn’t teaching English at his alma mater, Oswego High School, you might find him tackling line edits for his next book. In June, HarperCollins published his debut middle-grade novel, The Civil War of Amos Abernathy. His second book, Matteo, is due to be released next summer.

On his love for books as a kid: “In my very early years, I was homeschooled, and my mom was a fabulous teacher,” Leali says. “She read to us constantly, and I was completely captivated by the stories we brought home. We were always at Anderson’s [Bookshop in downtown Naperville] or at the library.” When Leali learned how to read on his own, he says it felt like he had gained a superpower.

Creating books as a kid: When Leali wasn’t reading, he was making his own books; common sources of inspiration for his characters included his dinosaur toys and Beanie Babies and his own fantastical doodles. “My mom always had all this construction paper and computer paper and markers and crayons, and we even had adhesive laminate that really made whatever I did look like a finished product,” he says. “Even if it was just with gift-wrapping ribbon or string or yarn, we would bind it all up and it became a book.” When Debbie Dadey, author of The Bailey School Kids series, visited his first-grade class, Leali felt his future was sealed. “I was hanging on every single word she said. I knew, I’m going to find a way to do this. Someday, my book is going to be on the bookshelf at Anderson’s.”

All about Amos: The Civil War of Amos Abernathy centers on an openly gay, history-obsessed 12-year-old boy who volunteers as a 19th-century historical reenactor. “When a new boy shows up to volunteer at the living-history park, Amos has butterflies and he realizes he’s having his first real crush,” Leali says. “His crush, Ben, comes from a pretty homophobic family, and Amos starts to wonder, Where does that come from? and it starts generating these questions like, Where is the history of people like me? He goes on a mission to prove that the LGBTQ+ community always has and always will exist in history.” Amos’s research leads him to Albert D.J. Cashier, an actual historical figure: The Civil War veteran was assigned female at birth, identified as male throughout his life, and spent time living in Illinois. “Amos starts journaling letters to Albert,” Leali says, “and Albert becomes his confidant, his inspiration, his everything, as he confesses and tells his secrets and explains his day and reflects on what’s going on his life.”

From fantasy to contemporary fiction: Fantasy writing had been Leali’s focus. His first manuscript his agent pitched to publishers was a novel from that genre. However, when it didn’t get any bites, Leali was inspired by his mother and grandmother’s encouragement to “write what you know.” Says Leali: “I started thinking about who I was and stories that I wished I had read when I was a kid, things that maybe would have made my life a little easier.” He reflected on his time volunteering as a historical reenactor at Naper Settlement from fourth to seventh grade and his own story of disclosing that he was gay. “It took me a very, very, very long time to come out. It wasn’t until my sophomore year in college. And it was a very painful experience. I kept thinking, What if I’d had some other way of seeing myself in the world or recognized what was really going on inside me at an earlier age?” He also realized he knew little about LGBTQ+ history pre-Stonewall. “So, I was like, ‘What would a kid do?’ I Googled ‘19th-century gay people.’ ” With those inspirations at play, the story of Amos began to take shape.

On the most surprising thing about publishing a book: Leali has worked with books in different capacities, first as children’s manager at Anderson’s Bookshop in LaGrange and then as a marketing specialist for Sourcebooks, an independent publisher in Naperville. “For as much time as I spent around books, I still wasn’t prepared for the emotional journey that publishing a book is,” Leali says. “It’s not just the act of writing and how much it takes out of you to write the words, but you’re also putting yourself out there. I thought, I’m a teacher, I have pretty thick skin. Teenagers have no filter. I’m finding that with my book, it feels like my child, and I’m so proud of it, and it’s such a strange feeling to have people both praise and criticize it and to feel the roller coaster of pride and joy and then disappointment, sometimes all at once. It has been more taxing than I expected, but at the end of the day, it’s very worth it. I’m just so proud of what this book is, and it’s what I’ve been working for since I was a kid.”

Critical kudos: The Civil War of Amos Abernathy had received a starred review from the American Library Association’s Booklist and a second from the School Library Journal. It is also a Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection and was recognized on the Indie Next List.

For his readers: “For members of the LGBTQ+ community, I hope that they feel seen and celebrated,” Leali says. “And for those who are questioning or just starting to wonder, I hope that it creates an opportunity for them to feel safe and explore those feelings just with themselves. I really hope that for young readers who are gay or lesbian or trans or nonbinary, that they’ll feel validated when they see this book on the shelf. My protagonist, he’s got the updated pride flag on his shirt [in the cover illustration]. I hope they see it and they know that they are worth taking up space.” For those outside the LGBTQ+ community, Leali says he wants the book to provide “an opportunity for them to grow in their empathy and really put themselves in someone else’s position for just a little bit and see what is possible when you do that—that you can grow in your ability to care and respect so much more.”

His goals as a high school teacher: “I hope that what I create is a very authentic and genuine space for my students to grow and explore books,” he says. Carving out even a small amount of time for independent reading has been positive for students. “To be able to provide eight minutes to be still and quiet their minds and really focus on a singular task is calming, and it really helps their ability to focus,” Leali says. When students finish a book, he invites them to record it on a colored note card to post on the classroom wall. “It was fun to see that wall grow. It becomes this centerpiece of, ‘Look how much we’ve read collectively.’ ”

Jennie Oh Brown

The entrepreneurial musician

Elmhurst resident Jennie Oh Brown, 53, is a professional flutist who recently joined Epiphany Center for the Arts in Chicago as artist-in-residence and artistic director. She’s also executive and artistic director of Picosa—a chamber ensemble she founded, which is now in residence at North Central College in Naperville—and is on the faculty at Wheaton College.

Her first notes: Oh Brown immigrated from Seoul, Korea, with her family as a child. She sang and played piano, violin, and string bass while growing up in the south suburbs, but it wasn’t until sixth grade that she chose the flute. “I don’t entirely know why. I remember the music teacher said I was too old—which now I think is complete insanity,” she says. “So I was really interested and probably annoying my mom. She found a private teacher for me, which is really actually the ideal way to start.”

Falling fast for flute: “I became very serious very fast,” she says. “I remember sitting at the kitchen table with my parents when I was a sophomore in high school, and I declared I wanted to do music [for a living].” After her junior year in high school, Oh Brown attended a summer music program at Michigan’s Interlochen Center for the Arts and decided to stay for its residential music program, Interlochen Arts Academy. “In my mind, it was really like the beginning of my life. It was really the moment where I focused and really dedicated my work to my future music career.” She went on to major in music at Northwestern University and earned her master’s and doctorate at Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York.

Carving her career path: While studying at Eastman, Oh Brown was offered a dual teaching assistantship in flute performance and musicology. “Up until that point, I had really only done flute performance. All of a sudden, I had to divide my energy between teaching an academic subject and continuing with my playing, and initially it was pretty overwhelming. I worked really hard and having the opportunity to do multiple things at once, I found, was actually quite fulfilling.” Oh Brown credits this experience with inspiring her career path of balancing performance with teaching. She joined the faculty at Wheaton College in 2002 and also taught for 10 years at Elmhurst University, all the while pursuing performing opportunities, including substitute gigs with the Lyric Opera of Chicago and Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra.

Hosting a festival in a pandemic: Oh Brown served as artistic and executive director for the 2021 Ear Taxi Festival, which she describes as “a citywide celebration of Chicago music in the 21st century.” Originally planned for 2020, the fest spanned from July to November of last year and involved 600 musicians in 100-some events, both in person and virtual. “For so many musicians, that was the first time they were onstage since the pandemic had hit,” she says. “It’s something that I think I will forever look at as a milestone in my career.”

Classical music’s racial homogeneity:“The thing about classical music is that it has a diversity problem,” Oh Brown says. “And part of that is that it comes from the European tradition. But even as an industry, it has a diversity issue, and that’s something I was not as aware of in school as I am now several decades outside of school. So that has become a central point of, frankly, determination for me. And that was very clearly at the center of our mission for the Ear Taxi Festival. If you really want the best art, you’re going to seek out all the voices, period. Beethoven is great. I love Beethoven! But when all you do is Beethoven, how much are you missing out on? Nothing makes me happier than walking into a concert and hearing something that’s completely new and phenomenal.”

Her commitment to championing diversity: “I feel a particular agenda in my professional life of wanting to blow those doorways wide open for everyone, “Oh Brown says. “I’m sort of like [Epiphany’s] newest gatekeeper, and I’m going to blow that gate wide open and make sure it’s accessible to everyone. There are all sorts of reasons why opportunities are closed off to certain people. And I just want to see all of those go away.”

A career highlight: Chicago Tribune music critic Howard Reich featured Oh Brown’s second solo album Giantess on his 2019 best albums list. “I thought it was insane because another person on the list was Yo-Yo Ma, and many other very illustrious musicians,” she says. The album is dedicated to her grandmothers; one lived to be 112 and the other to 88 after battling cancer. “They were just my inspiration in many ways, so when I put together the programming for my album, even though they were both really the sweetest grandmothers anyone could ask for, I wanted an album that spoke more to their strength and power as women.”

Photos courtesy of Ross Feighery (Blanco), Rafael Blanco (Murals), Genna Brems (Leali) and HarperCollins (Book Cover), Marc Perlish (Brown)