Epidemic of Bias

By Naperville Magazine

January 2020 View more 630

By Christie Willhite

On a rainy night in November, a crowd of concerned local residents gathered at Naperville’s Riverwalk with a singular message: Hate has no home here.

They wanted to say it aloud, to make the statement clear. Because as cities across the nation have suffered violence fueled by hate, Naperville too has felt the impact of racism with seemingly increasing frequency.

Here at home, it’s not the anonymous aggression carried out by members of the alt-right movement. It’s close and personal. It might be the cashier, the couple eating at the next table, the child sitting next to yours in class.

“I would be quick to acknowledge there is something happening nationally influencing what is happening locally,” says Stephen Maynard Caliendo, dean of North Central College’s College of Arts and Sciences and a political science professor with a focus on race and equality politics.

“Four years ago it was wildly unfashionable to display racism publicly,” he says. “People are much more comfortable embracing white nationalism and supremacism and embracing the beliefs of those movements.”

In the last year, Naperville has experienced a series of independent incidents that have prompted some residents to take a closer look at how the city’s increasingly diverse population interact with each other.

In July, a convenience store cashier told two Hispanic customers from Naperville to go back to their country. In October, two white diners complained about a multiracial group being seated near them in the restaurant. And in November, a white student was charged with hate crimes for targeting a classmate with a racist post at one high school, while another school investigated a student using a racist epithet during a class activity.

“What’s going on in Naperville is not unique to Naperville,” resident Kim White says. “What’s going on is not new to those of us who’ve experienced it. It’s maybe more to the fore.”

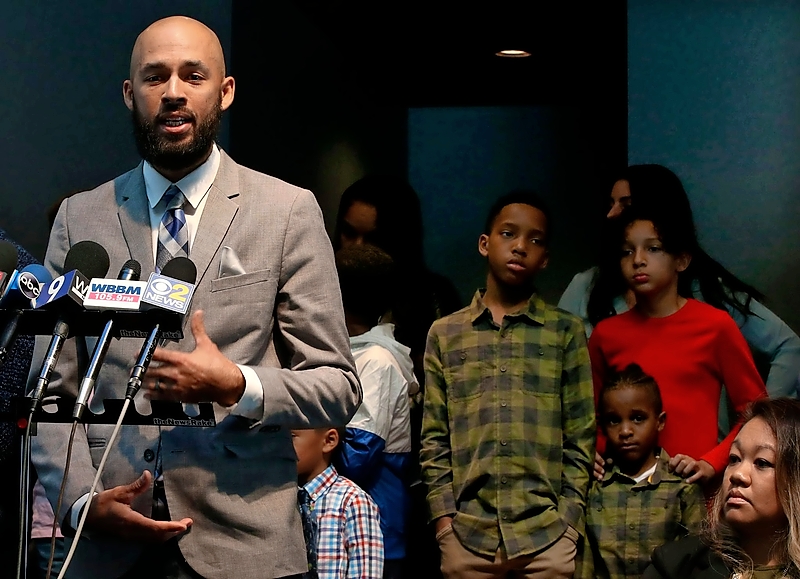

“The key for us as a community, and as community leaders, is to speak out when we see it,” says Benny White, Kim’s husband and Naperville’s only black city council member. “The attitude has got to be, ‘not in my town.’ ”

When he sought election in 2017, White ran on a platform of bringing the community together to create trust among community members and civic leaders, he says. To that end, he launched Naperville Neighbors United, an ongoing series of informal discussions to explore how race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other attributes affect residents’ experiences living and working in Naperville.

“Naperville is a top city in the country. It’s a natural reaction to say [racist incidents are] not reflective of our town. There’s a tendency to be defensive,” he says. “We need to have the conversations that get people out of their comfort zones.”

A recent Naperville Neighbors United discussion featured participants sharing personal stories of everyday racism, of other’s actions that belittled them or made them feel unwelcome. Much of the audience listened in tears, White says.

Both Benny and Kim White believe sharing experiences goes a long way toward fostering understanding. When their children were called racist names, the couple would talk with the other families to explain why the terms are offensive and how the entire family had been hurt. Most often, the other parents were receptive, Kim White says.

“If people really want to dive deep, I ask what their Friday night looks like. If you’re enjoying a night of food and you don’t have a diverse group at your table, it’s hard to get that perspective,” she says. “When you know a variety of people, you tend to remove some of those biases you might have.”

With the growing diversity in Naperville, parents can broaden their circle by building relationships with the parents of their children’s friends, classmates, and teammates, suggests Kim White.

Caliendo encourages reading works by authors of different backgrounds, which can also foster understanding (see sidebar). He encourages people to listen to speakers, see musicals and plays, and attend cultural events in the community. North Central can be a resource, especially in January as the college celebrates the life and teachings of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., he says, and in February as it observes Black History Month. “We can credit the Baby Boomers with saying we need to love everyone,” says Caliendo. “We’ve got to be willing to put the work in to make it happen.”

Gaining Perspective

North Central College professor Stephen Maynard Caliendo suggests the following readings and authors for people interested in expanding their understanding of race and justice in America. Caliendo, a political science professor, is dean of North Central’s College of Arts and Sciences and is co-founder and codirector of the Project on Race in Political Communication.

“Letter From a Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King Jr.

Ain’t I a Woman and other writings on black feminism by bell hooks, the pen name used by Gloria Jean Watkins

Between the World and Me (above) by Ta-Nehisi Coates, as well as his columns in the Atlantic

Writings by Harvard University professor Cornel West, author of 20 books, including Race Matters and Democracy Matters

The Wrong Side of History

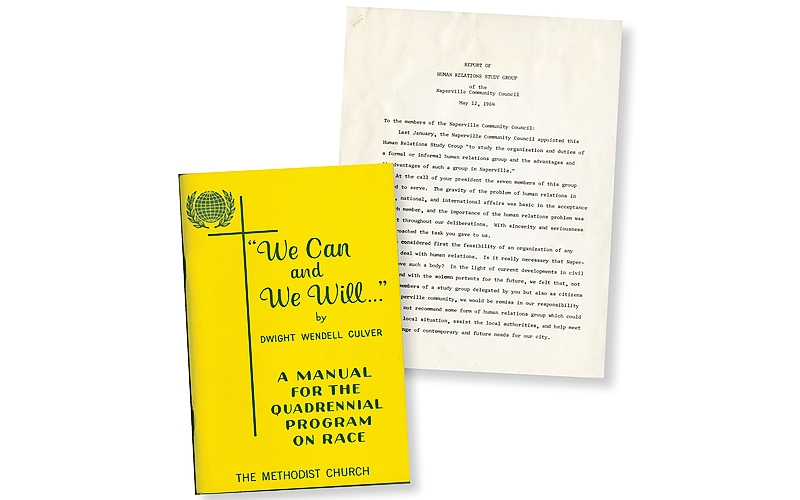

Naperville is a town with an annual Indian cultural festival, a Chinese school, and volunteers dedicated to celebrating the community’s diversity. But the city’s history hasn’t always been one that reflected inclusion.

Recent research indicates that through much of the first half of the 1900s, Naperville likely was a “sundown town,” says Naper Settlement vice president Donna Sack. People of color would have been allowed to work in town during the day, but aggressively discouraged from living here—both through unwritten practice and restrictive real estate covenants, she says.

The Naper Settlement staff is researching the last century, as the museum shifts from presenting only the story of the community’s pioneer settlement to presenting a more complete history of Naperville, Sack says.

The evidence lies in community censuses: In 1880, the census shows 10 African Americans living in Naperville. Yet both the 1900 and 1940 censuses showed just one African American resident in Naperville, though the total population doubled from 2,600 to 5,200 over the time frame. After the federal Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 and codified locally the same year, the 1970 census showed 43 African American residents in a community of 22,600, Settlement research shows.

“It’s important to have a baseline understanding of our community’s past, as these topics are being talked about more,” Sack says.

Using a federal grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Naper Settlement is leading Naperville and five other towns in the north and west parts of the country as they research how sundown practices—and housing discrimination—influenced the communities’ development. Together, the participating organizations will create an online exhibit that will be available in 2021, she says.

“Each town has a unique story, but we share the common element of exclusion,” she says. “It’s an amazing opportunity to work around this topic and be able to have a conversation about it. Knowing our history is a healthy thing.”

Photo by Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune. Cover Courtesy Spiegel & Grau/Penguin Random House

Documents Courtesy of the Naperville Heritage Society Archives