Exposed

By Naperville Magazine

June 2019 View more Featured

Scientist David Raphael unwittingly gave his life for his country due to exposure to radioactive materials. His family now wants to educate others about the plight of thousands of these Cold War patriots.

By Christie Willhite

During the most heated moments of the Cold War, Caroline Senetar’s father was doing his part to keep our country safe.

As generations before him had contributed to the efforts by joining the military or working to support soldiers from the home front, Senetar’s dad was a government physicist in the 1960s researching nuclear weapons to keep the United States ahead of the Soviet Union in the nuclear arms race.

But while the Naperville woman is proud of her father’s service to his country, it’s the rest of his story she draws attention to, in the hopes of helping others.

Well after Senetar’s father, David Raphael, died from cancer, she learned that his illness could be traced directly to the radiation he had been exposed to decades earlier while working at a national laboratory outside of San Francisco.

Raphael is one of tens of thousands of Americans who worked for or with the U.S. Department of Energy from the 1940s forward who were exposed to radiation and illness-inducing chemicals and substances long before anyone realized how the exposure would affect employees’ health.

Those employees and their families need to know, Senetar says, that the federal government recognizes the service of employees and contractors and honors the sacrifices they made through a program that covers their medical expenses and offers compensation for their loss.

Raphael’s story is just one of many in Illinois and in communities stretching from coast to coast.

Coming out of World War II, relations between the United States and the Soviet Union were uneasy at best. The U.S. already had shown the world its atomic bombs at the end of the war. Once the Soviets detonated their first atomic warhead in 1949, the Cold War nuclear arms race was on.

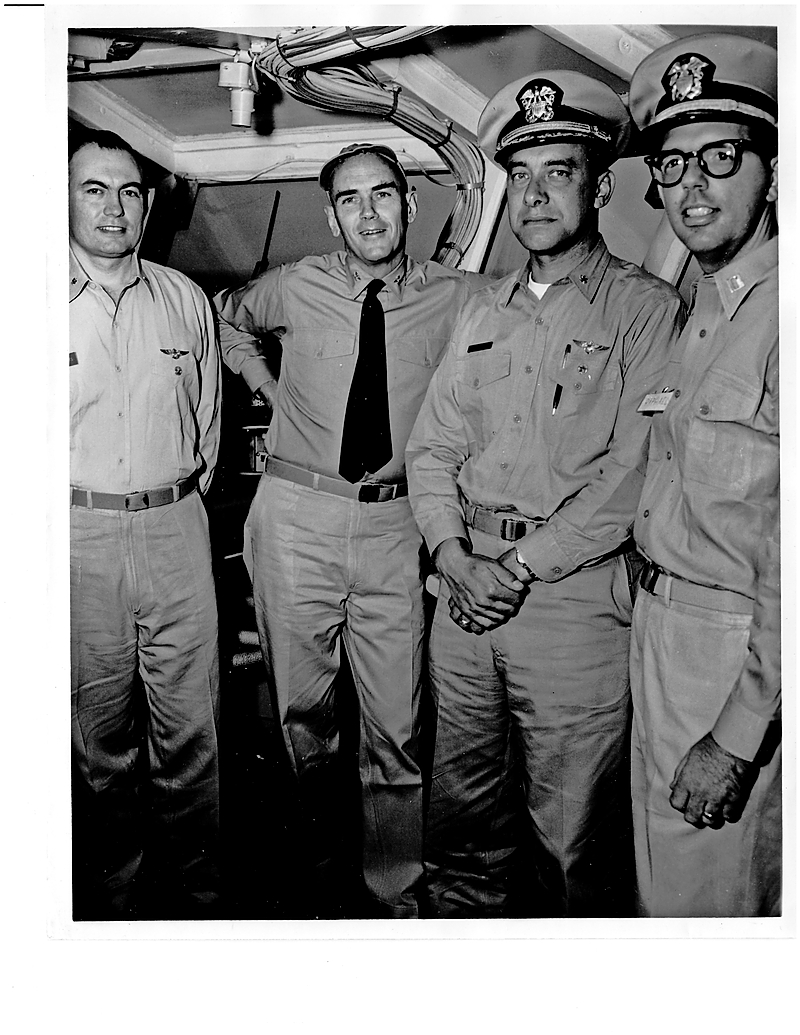

Against this political backdrop, David Raphael earned a degree in physics from the University of San Francisco and entered the U.S. Navy in 1956. Officer training led to nuclear weapons training and then to a 1958 deployment on the USS Hornet, where Raphael served as a nuclear supervisor. After deployment, Raphael became a nuclear weapons training officer, instructing naval officers in nuclear theory and classified communications and publishing 11 nuclear manuals.

With his physics degree and experience with the navy’s nuclear weaponry, in 1961 Raphael secured a job as a physicist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California, about an hour outside San Francisco. The facility had opened in 1952 to be a “new ideas” laboratory that would augment the nuclear research of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, according to the Livermore lab’s website.

Raphael worked at Livermore during the early 1960s, when scientists at the facility were looking to outpace their Soviet counterparts to develop and stockpile weapons that would deter our Cold War adversary from striking.

The scientists and staff at the Livermore lab and Los Alamos were part of a network of government employees, contractors, and subcontractors that stretched across the country. From those who mined, stored, and transported the raw materials to those who developed them into weapons and manufactured warheads, all were doing their part to safeguard the nation against the threat of Soviet aggression.

“In my opinion, everyone who worked then in the classified labs—and in support of them—was a patriot. I think of them as the Cold War patriots,” Senetar says. “I don’t think they had any idea of what they were exposed to and the long-term effects. How would they have known anything like that?”

Today, we know much more about the harmful effects of exposure to radiation and chemicals, but when Senetar’s dad was researching at the Livermore lab, science knew only of the powerful potential of substances like uranium and plutonium and the promise the resources held for military weapons and, more broadly, as sources of energy.

Raphael himself worked until 1967 in Livermore’s Radiation Material Laboratory, largely dedicated to the design of the Polaris nuclear warhead, Senetar says. A U.S. Department of Labor database lists about 240 substances that a Livermore physicist may have been exposed to. Some items on the list, like oxygen and rubbing alcohol, are normal substances to which any of us could have contact. But Raphael likely was exposed to radiation from working with uranium and plutonium.

In 1997, a full 30 years after leaving the Livermore lab, Raphael was diagnosed with liver cancer and later, colon cancer. He died February 14, 2001, at the age of 67.

Raphael’s story is one replicated in families across the country, families with a loved one who once worked with or for the U.S. Department of Energy who was suffering from or had died of cancer.

Lawmakers eventually recognized the high incidence of cancers and other exposure-related illnesses. In October 2000—just months before Raphael’s death—Congress approved the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act. The intent is to pay the medical expenses of affected workers, reimburse them for lost wages, and compensate them or their survivors.

Though she was executor of her father’s estate, Senetar didn’t learn of the program until 2015, when a third party offered to investigate whether her father’s experience would qualify for compensation. She didn’t believe the program was real, she says, until she started investigating.

“The more I learned, the more unbelievable it became,” she says. “I had no idea this existed, no idea of the number of people involved and the number of facilities involved.”

To apply for survivor’s compensation, Senetar needed evidence that her father had worked at the Livermore lab and that he’d been diagnosed with one of the 22 covered cancers or diseases, as well as family records showing their relationship. Fourteen years after his death, she set out to re-create his life.

“He didn’t talk about work. Everything was classified,” she says. “Later, I never asked questions. I never thought to. You talk, but your conversations are about what’s happening today, not what he did years ago.”

By talking with her uncle, poring over paperwork and reading her dad’s notes and journals, Senetar began putting together the pieces of her father’s career. With the right documentation, she was able to obtain employer names and specific dates from the Social Security Administration, giving her the evidence that Raphael had worked at the lab during the period covered by the compensation act.

Further research through her parents’ documents led Senetar to the doctor and hospital where her father was initially diagnosed. The hospital’s records clearly stated Raphael’s diagnosis.

“The minute everything pulled together, it was such a clear picture of who my father was and what had happened to him,” Senetar says. “It was truly a labor of love.”

The connection between Raphael’s illness and his work as a nuclear physicist may seem like a straight line, but Senetar worries that the links may not be as direct for other families who would be eligible for benefits under the compensation act.

Someone who loaded a railcar thousands of miles from a national laboratory, or someone who worked as a custodian or secretary, may not even realize they were exposed, she says.

The Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act recognizes more than 300 affected sites nationwide, according to a U.S. Labor Department spokesperson.

Of those, 79 locations nationwide—including five in Illinois—are designated as Special Exposure Cohort sites, meaning that nearly everyone who worked onsite for at least 250 days is eligible for compensation if they have been diagnosed with at least one of the 22 specified cancers, as Raphael was.

“It’s labs, universities, chemical companies, manufacturing, railroads,” Senetar says. “It’s a lot of people like that who never would’ve thought they were exposed. They need to know about this.”

The program provides a lump-sum payment of up to $150,000 for qualified employees or their survivors, and pays the related medical expenses for employees as they’re treated for the specified diseases, according to the program’s website.

Affected workers outside of the designated Special Exposure Cohort sites are eligible for similar benefits that are allocated based on the amount of exposure they may have experienced and how pervasive their illness is, the labor department spokesperson says.

Senetar advises families to look into the compensation program if there’s even a hint that someone they know may have been affected.

As medical knowledge grows about the links between exposure and illness, and as the federal government gathers information on the sites and employees’ experiences, sites are added and exposure periods are updated.

And while some sites’ exposure periods are firmly set during the Cold War, others—like the Livermore lab and Los Alamos—extend into the 1980s and 1990s.

Since the compensation program began, the government has awarded more than $16.1 billion in benefits on behalf of 122,760 individuals nationally. In Illinois, nearly $220.9 million has been awarded on behalf of 3,445 individuals.

The compensation program is run by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs. To learn more, visit dol.gov/owcp/energy.

Questions about specific cases should be directed to the Paducah Compensation Resource Center, 125 Memorial Drive, Paducah, KY 42001 or by telephone at 866.534.0599.

Illinois exposure sites

On December 12, 2006, then Senator Barack Obama (below) met with former employees of two Illinois nuclear weapons plants, who testified before a federal advisory board in Naperville regarding compensation for employees with qualifying illnesses. Five Illinois sites are currently identified as Special Exposure Cohorts, where exposure was prevalent:

Allied Chemical Corporation, Metropolis

Atomic weapons employees who were monitored or should have been monitored for ionizing radiation while working between January 1, 1959, and December 31, 1976

Argonne National Laboratory–East, Lemont

All employees of the Department of Energy or its predecessors, as well as the contractors and subcontractors, who worked onsite between April 10, 1951, and December 31, 1957.

Blockson Chemical Company, Joliet

All employees of Atomic Weapons Employers who worked onsite between March 1, 1951, and June 30, 1960.

Dow Chemical Co., Madison

All employees of Atomic Weapons Employers who worked onsite between January 1, 1957, and December 31, 1960.

Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, Hyde Park

All employees of Atomic Weapons Employers who worked at the lab between August 13, 1942, and June 30, 1946.

In addition, employees at the following Illinois companies may be entitled to compensation based on their position, employment dates, chemical exposure, diagnosis, and other factors:

- null

- Armour Research Foundation

- Crane Co.

- Fansteel Metallurgical Corp.

- Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory

- General Steel Industries

- Great Lakes Carbon Corp.

- GSA 39th Street Warehouse

- Kaiser Aluminum Corp.

- Lindsay Light and Chemical Co.

- Precision Extrusion Co.

- Quality Hardware and Machine Co.

- Sciaky Brothers Inc.

- W.E. Pratt Manufacturing Co.

Note: A current list of known Department of Energy contractors and subcontractors is available at btcomp.org.

Source: U.S. Department of Labor/Office of Workers’ Compensation Program

Photos courtesy Caroline Senetar, Scott Olson/Getty Images, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory