Prepare for the Invasion

By Naperville Magazine

Appears in the May 2024 issue.

By Kelli Ra Anderson

Cicada-geddon is upon us this spring

Parts of Illinois will be the envy of entomologists across the globe this spring when they experience a very rare spectacle: the simultaneous emergence of two very large (and very loud) periodical cicada broods. The last time the 17-year Northern Illinois Brood (aka Brood XIII) and the 13-year Great Southern Brood (Brood XIX) were in sync was more than two centuries ago when Thomas Jefferson was president. It’s been a minute.

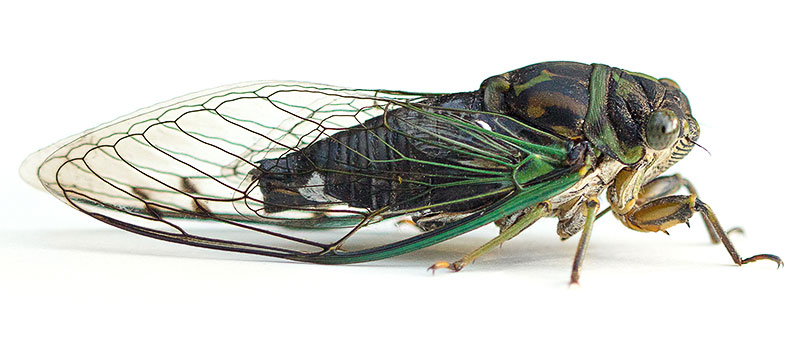

Unique to our part of the world, there are essentially two kinds of cicadas, annual (above) and periodical (right). The larger, more familiar dog-day cicadas, with their distinctive brown and green heads, appear each June. But smaller periodical cicadas live underground for several years before they suddenly emerge like clockwork when the soil warms up to 64 degrees at a depth of 8 inches, typically in late May or early June. At night the nymphs crawl up from the soil into trees to molt, shedding their exoskeletons (all those empty, crunchy cicada shells you’ll find). Emerging white and soft, the new adults will darken and harden during the night. The males will sing out their pulsing “cicada-ian” rhythms to find a mate; the females will then lay their eggs—about 500 or so—in the new growth of woody plants. And the cycle starts all over again.

Although anticipated to spill out of the earth by the billions this year (between 50,000 and 1.5 million per acre in some areas), these alien-looking creatures are nothing to be afraid of. Yes, their songs are loud. At 105 decibels (think: lawnmower, leaf blower, chainsaw), they can be a bit much. But they neither bite, sting, nor harm our gardens. In fact, they are quite beneficial. Living exclusively near trees, their tunnels aerate the soil, and they provide an-all-you-can-eat buffet for birds and other wildlife—including humans. (Adventurous foodies say they taste like almonds.)

“When they’re nymphs hanging out in the soil, they drink sap from tree roots,” says Kacie Athey, assistant professor and specialty crops entomologist and extension specialist with the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “But with [mature] cicadas, they’re not going to be a big problem for crops.” Contrary to popular misconceptions, she emphasizes, they are not related to crop-destroying locusts.

Along with wide-set red eyes with black heads and thoraxes, the cicadas sport orange-tipped wings that are delicately veined and shimmer like leaded-glass windows. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, of course.

Because the 13-year brood emerges in southern Illinois and the 17-year brood sticks to the north, only one sliver of the state is likely to host both. “The bigger hype this year is that these broods will be at the same time and year, but they aren’t overlapping much,” says Amber Ross, naturalist with the Forest Preserve District of Kane County. “There might be slight overlapping in Springfield—good luck to them. But we are only going to see the 17 years in our area.”

That said, the northern brood can be overwhelming all on its own, but there will be plenty of areas where there will be few to none. So, how will you know what to expect?

Location, location, location. Only areas that had cicadas 17 years ago with trees and soil that have remained undisturbed–free from development–are likely to have them again. Maps like those by Cicada Mania (cicadamania.com) identify areas likely to see the most. Another resource is the Illinois University Extension site (extension.illinois.edu/insects/cicadas). And don’t forget to check out local educational programs.

DID YOU KNOW?

Cicada Data

● Cicadas aren’t locusts, and they don’t eat crops or plants.

● Cicadas are among the longest-living insects in the world.

● Do not use pesticides on cicadas; pesticides also kill crucial pollinators and harm or kill pets and wildlife that may feed on the poisoned cicadas.

● Protect smaller trees (1 to 3 years old) with netting to prevent damage when female cicadas cut open branches (called flagging) to lay their eggs. Flagging may scar but usually will not hurt healthy, mature trees.

● The next dual emergence of 17-year and 13-year cicadas will be in the year 2245.

● A great source of protein, cicadas have been eaten by humans for thousands of years. Yum!

Photos: iStock