Pulling Through

By Naperville Magazine

July 2021 View more Featured

Countless restaurants shut their doors forever due to the pandemic. But for three resilient chef-owners, sparks of internal creativity and the support of local communities reinforced why they’re so proud to call the suburbs home.

Story by Peter Gianopulos | Photography by Jeff Marini

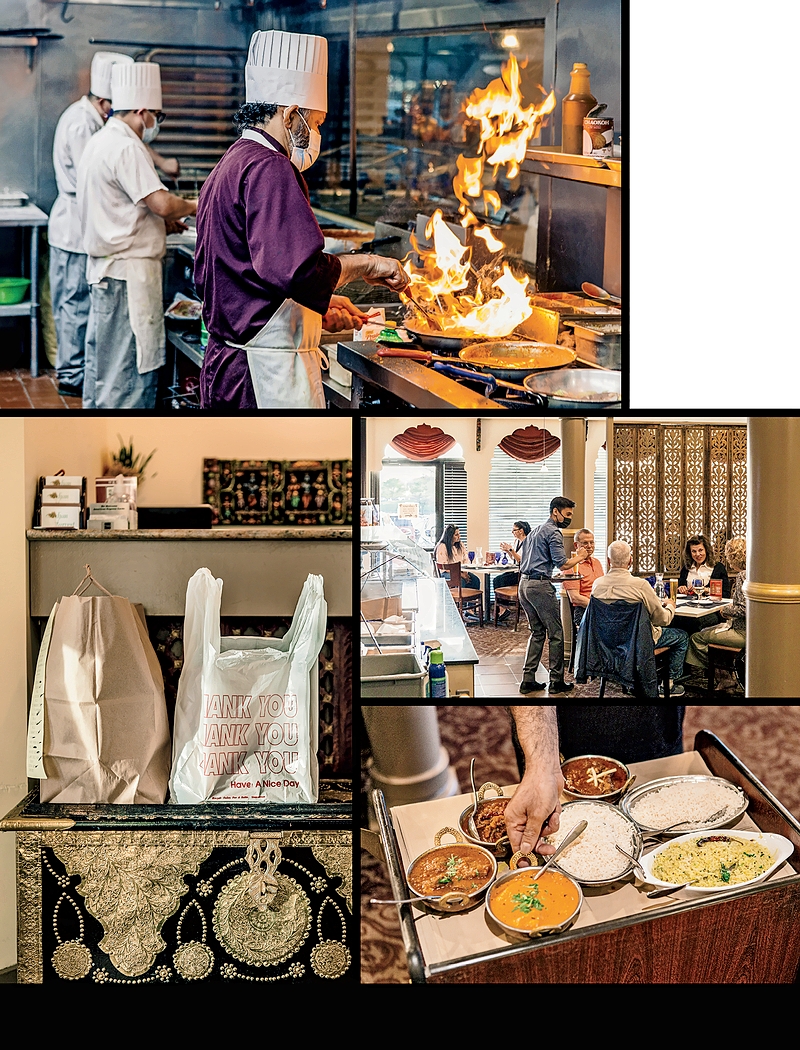

Sanjeev Pandey of Indian Harvest in Naperville; Chris and Mary Spagnola of Milkstop Café in La Grange; and Paul Virant of Vie in Western Springs, Vistro Prime in Hinsdale, and Gaijin in Chicago

One long unrelenting existential crisis.

That’s the only phrase that Sanjeev Pandey, the owner of Indian Harvest in Naperville, feels is accurate—and dire—enough to describe the pressures of running a restaurant last year.

Navigating mini crises—a line chef calls in sick, kitchen equipment breaks down, a crate of cremini falls off a truck—comes with the job. But last year ushered in unprecedented new challenges. Enforced shutdowns. PPP loans. Employee furloughs. And, worst of all, the extended din of all those empty dining rooms—devoid of food, families, and fun.

“It was like being caught in a perfect storm,” says Pandey. “My mind went into pure survival mode. We eliminated all nonessential expenses, ordered supplies in more limited quantities. In the end, you just do everything you can to try and stay afloat.”

There was the $10,000 he invested in a new point-of-sale system last March, just as the statewide restaurant shutdown was announced. And the logistical nightmare of transforming a 4,100-square-foot sit-down Indian restaurant into an efficient takeout operation in mere weeks.

Nevertheless, the memories Pandey recalls most clearly involve neither panic nor fear, but rather the outpouring of community support that greeted him during the apex of the crisis.

The emails from customers arrived first, flooding his inbox last spring. Some were nostalgic, recalling memorable dining experiences. Others were more personal, thanking Pandey for kindling their love for Indian cuisine. But every note, in one form or another, offered some variation of the same theme: “Stay strong. We’ll be there for you when you need us.”

As Indian Harvest shifted to carryout, some regulars seemed to make it their mission to help support the restaurant. Some ordered food, like clockwork, every single week. Others opted to pay in cash to eliminate credit card processing costs. And some left tips so generous it was difficult to differentiate the gratuities from the payments.

“It was such a heartfelt outpouring of support,” says Pandey, who opened the initial iteration of Indian Harvest in 1998. “Whenever I would come out of the kitchen or deliver food to someone’s car, people would pull me aside and say, ‘We’ll do everything we can.’ And they did. It’s sort of strange to say this, but it was honestly one of the most gratifying experiences of my entire restaurant career.”

Pandey is not alone in voicing that sentiment. Although many restaurants that temporarily shuttered last March will never open again, a fortunate few have found the means to stay open. Often their survival was a byproduct of bursts of innovation coupled with local support, reminding restaurateurs why they chose to enter this notoriously high-stress, low-margin business in the first place.

CHRIS AND MARY SPAGNOLA, owners of Milkstop Café in La Grange, share vivid memories of monitoring COVID-19’s spread by sneaking quick glances at the TV over their bar during service. When reservations for their cozy seasonal American bistro, which opened in October 2019, waned last winter, they could sense danger on the horizon. But it wasn’t until St. Patrick’s Day 2020 that it became clear the rumors of statewide shutdown were bound to become a reality.

“Every day was a nail-biter—and still is,” says Mary. “It was sort of a controlled panic in the early days. There were just so many unknowns to deal with. Our first thought was simply: We have to keep going and come up with new ideas for the restaurant. Because if you just stop, it’s hard to rebuild any kind of momentum.”

Not wanting to fully close for a single day, the Spagnolas immediately launched a fresh slate of carryout family-meal offerings—half-pans of lasagna, roasted chicken, and meatloaf for four to six people—on the Monday following Illinois’s shutdown order.

From there they just kept ideating away, trying to muddle through. When La Grange loosened its restrictions on serving to-go cocktails in June, they reached out to mixologists to develop a menu of travel-proof cocktails. Soon they were making their own bitters and converting their beloved blackberry mint syrup—once used as an ice cream drizzle—into the base for a portable whiskey smash.

By January, as the snow fell and temperatures dropped, the Spagnolas couldn’t help but wax nostalgic about their younger years, when they worked as chefs aboard a private yacht. One afternoon, while docked at Isla Mujeres in Mexico, the couple experienced their first taste of quesabirria, a life-altering street-food delicacy that blends the gooey cheesiness of quesadilla with the meaty crunch of a plancha-fried taco.

The Spagnolas could think of no better midwinter mood-lifter than biting into a piping-hot, fresh quesabirria. So they decided to conduct an experiment: They’d fry up their own goat-beef quesabirria and sell them out of the back of their kitchen for $5 a pop.

To avoid the dangers of too much foot traffic, they adopted a speakeasy business plan. Customers could knock at the back door, put in their order, and the Spagnolas would sling them hot quesabirrias fresh off the griddle.

It didn’t take long for one particularly loyal customer, Louise Graff, to come by for a sample. She tried. She cooed. She posted. Her mention caught the attention of Krissy Joseph, a moderator of the La Grange Area Restaurant Take-Out & Delivery page, who further promoted it with Facebook live shots, photos, and community engagement. Before the Spagnolas knew it, their back-door quessabirras were a community sensation.

“Once she posted, we had a line down the block for the next month,” says Chris. “When we first started, we had to do a limit of six per person, and I remember seeing people order six and then go straight to the back of the line to get six more.”

The only endearing benefit, says Mary, of the pandemic experience was being able to watch the couple’s two young sons—ages 5 and 7—run around the restaurant, pretending they were filling in as Mom and Dad’s servers. Other afternoons, between remote school lessons, they’d saddle up to the bar and watch cartoons as their parents filled orders.

“We had some laughs,” says Chris. “I can remember some customers walking in to get pickup and they’d look up and see Nickelodeon on the TV and our two young kids sitting at the bar. It was a unique year to say the least.”

NOT FAR AWAY IN HINSDALE, Paul Virant had his hands full trying to keep his mini empire—Vistro in Hinsdale, Vie in Western Springs, and the newly opened Gaijin in Chicago—chugging along. As the spread of COVID accelerated in March and the likelihood of a shutdown increased, Virant decided to adopt a “wine glass half full” approach to the crisis.

“If we did have to shut down, I had a list of redecorating jobs that I thought I’d finally have enough time to get done,” says Virant.

It wasn’t until he drove down to Gaijin one Wednesday, finding that the normally bustling Japanese izakaya was virtually empty. When he stepped outside, strolling around Fulton Market, he knew tough days were ahead. “It was like the apocalypse hit,” he says. “There was literally no one around and absolutely nothing going on.”

Back at his suburban restaurants, Virant attempted to shift his existing menu to carryout, but he quickly sensed that many of his employees had safety concerns about coming in. It was better, he surmised, to shut down the restaurants completely for a few weeks and keep his management team on payroll to devise a path forward.

“It was unprecedented,” says Virant, of his staffing decisions. “There was no way, at least for me, to make all the decisions we needed to make without collaboration. Given all the issues, I needed a kind of task force.”

Virant not only brainstormed with his staff about new ideas, he also reconnected with fellow chefs and colleagues about a host of issues, from ever-evolving PPP loan rules to navigating rent reduction. By May, his chefs were positively brimming with potential food ideas that could be tailored to at-home dining.

Over the summer, Vie launched a series of at-home dining kits. Some were DIY three-course meals that required simple assembly and a bit of cooking. To-go family food packages were devised for holidays, like Mother’s Day and Memorial Day, tiding the suburban restaurants over until they reopened for indoor dining.

Having long dreamed of offering alfresco dining for Vie, Virant realized that the state’s indoor capacity restrictions were a sign that he should act now. He erected a pergola strung with lights for his new patio, while introducing a dizzying array of new options when he reopened for indoor dining on June 26. The kitchen team baked whole pies and sold them every other week through a summer program called “Oh Pie Goodness.” Later, the restaurants sold customized wine packages. Then, by November, when new shutdown orders were announced, both Vie and Visto transformed into retail shops, selling gift boxes, holiday candy, and retail wine.

All three of Virant’s restaurants have survived, but not without a few services that he wishes he could wipe from his memory.

“It can be hard to open up and shut down and open up again. I think the low point for me was our first service at Vistro. It was just one night, but probably in my Top 10, in terms of bad services. Nothing went right, but they hung in there with us. We were lucky to have a bunch of customers for both restaurants that kept supporting us.”

As 2021 dawned, Virant decided to keep evolving. He’d always wanted to open a steakhouse. And given the fact that comfort food was pretty much diners’ only option for the year, he decided to transform Vistro into a full-fledged steakhouse, Vistro Prime. “The time feels right to me,” says Virant. “Personally, I like the traditional steakhouse experience. Your order a few classic cocktails, a few cuts and some sides. It can make for a memorable night out. I think people are ready for that now. It gives you options—you can splurge or just enjoy a night out as a family.”

At Indian Harvest, Sanjeev Pandey plans on making some pivots of his own. Thanks to what turned out to be that rather timely investment in its new point-of-sale system, as well as digital media efforts of his daughter—who came home from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to help—Pandey upended his traditional business model.

Prior to the pandemic, 80 percent of his revenue came from indoor dining, while 20 percent came via carryout. During the pandemic, Indian Harvest was able to completely reverse those numbers. All of this, it should be noted, was done without instituting any staffing furloughs whatsoever.

Although it’s hard to predict what the future will bring, Pandey suspects that one of the restaurant’s staples—its lunch buffet—may prove impractical moving forward. He worries about all the food waste it produces and whether remote work will dramatically eliminate the long midday work breaks that were more common prior to the pandemic.

That being said, Pandey is content to keep evolving. “That’s the nature of any business,” he says. “It’s always changing. You have to stay nimble and take a hands-on approach to make it in the long run.”

Over the years, he’s always been particularly proud of the large open window that allows his guests to peer into the kitchen as their meals are being prepared and assembled. That rather simple window, he says, has helped people from all walks of life appreciate the history, traditions, and love that are at the root of Indian cooking.

These days, he’s come to see that window from a different perspective. Standing there behind the glass, looking out into the dining room, he’s able to hear and observe something that most restaurant owners took for granted prior to COVID-19: The sound of forks scraping excitedly against dishes. The echo of laughter and chatter bouncing around the room. And the view of so many strangers, huddled together, joyfully enjoying their culinary creations.

“We have had guests coming to our restaurant for 22 years,” says Pandey. “It’s nice to know that we’ve become part of some people’s dining routines—that we’ve found a way to make inroads into people’s hearts.”